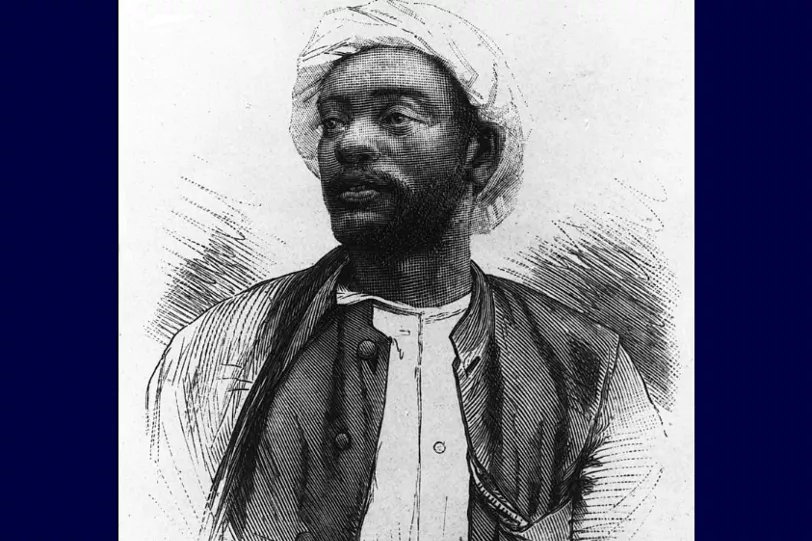

The last independent ruler, or kabaka, of the Buganda kingdom—now part of Uganda—was King Mwanga II, who has been a central figure in a propaganda battle since his reign began in 1884. Known for his relationships with both male and female lovers, critics have labeled him a deranged, murderous deviant, while supporters portray him as an early anti-colonial fighter. Modern LGBTQ+ activists have also pointed to him as evidence that queerness is part of Africa’s historical narrative.

Mwanga ascended to the throne at just 18, succeeding his father, Muteesa I. Reports suggest he had 16 wives and numerous male lovers, permitting homosexual relationships among his court. His lovers, regardless of gender, were referred to as bakopi, meaning “wives,” while he was called their nnanynimu or omufumbo, translating to “husband,” as noted by Rahul Rao in the Journal of Eastern African Studies.

Muteesa believed that forming an alliance with the British and welcoming missionaries would protect Buganda from colonial encroachment, trading influence for military support. He converted to Islam to strengthen ties with Swahili and Arab traders while allowing Protestant and Catholic missionaries into Buganda, reasoning that their rivalry would keep them preoccupied and unable to challenge his authority.

However, Mwanga was skeptical of his father’s strategy. As Destiny Rogers pointed out in QNews, he recognized that permitting missionaries into an African kingdom often led to increasing European influence, ultimately resulting in a loss of autonomy. Early in his reign, Mwanga began executing missionaries, killing 45 Christians between 1885 and 1887, many of whom were pages in his court who had converted to Christianity. The executions were often brutal, with some victims burned alive.

According to the legend initially reported by French missionary Père Simon Lourdel, Mwanga targeted young men for execution because they refused his sexual advances. Other European authors supported this narrative, arguing that the fact Mwanga did not execute other prominent court members who had converted indicated a personal motive.

Yet, is it merely a tale of a king seeking revenge against those who rejected him? In his 2011 biography, Mwanga II: Resistance to Imposition of British Colonial Rule in Buganda, 1884-1899, Professor Samwiri Lwanga-Lunyiigo contends that the real reason for the executions was that these pages were spies providing information to European colonizers. He also argues that they hadn’t genuinely converted to Christianity, citing Scottish missionary Alexander Mackay, who noted they hadn’t learned enough about the faith to truly convert.

“Many a life has been lost in Buganda for learning no more than the alphabet,” Mackay wrote.

Lwanga-Lunyiigo holds Christian leaders partially responsible for the killings, stating they had ample warning of the impending executions yet allowed the men to become martyrs. He cites Mackay again, who remarked that Bishop James Hannington, one of the first victims, was “executed as a courageous person but not because of his faith in our lord Jesus Christ.”

Despite this, Lourdel’s interpretation became the dominant narrative, and those executed are now known as the Uganda Martyrs. The 22 Catholic martyrs were beatified in 1920 and canonized in 1964, with a Catholic university in Nkozi, Uganda, named in their honor.

The Church of England leveraged its martyrs to garner support for the British Empire’s annexation of Buganda. Mwanga was deposed in 1888 by a rebellion backed by the British. His brother Kiweewa briefly took the throne before being replaced by another brother, Kalema, who ruled for just a year.

After negotiating with the British and ceding some power to the British East Africa Company, Mwanga was restored to the throne in 1889. By 1894, he was compelled to make Buganda a British protectorate, and three years later, he attempted to reclaim his kingdom through war. This conflict lasted only 15 days, leading to his deposition in absentia after he fled to German East Africa.

Mwanga’s life after his reign was short and brutal. Following another attempt to resist British control, he was captured, tortured, and exiled to the Seychelles. There, he endured further torture, was forcibly baptized into the Church of England, and renamed Danieri. He died in 1903, having been beaten and starved, at only in his mid-30s.

Uganda gained independence in 1962, but political instability ensued until a military coup in 1971. Some historians speculate that the British government may have facilitated this coup, which ultimately led to General Idi Amin’s rise to power, marking one of the bloodiest regimes in modern history.

Throughout Uganda’s history, Mwanga has been a figure of propaganda. Rao notes that his reputation has evolved over time. After Uganda’s independence, he was viewed as “an African patriot,” with those he executed seen as “imperial collaborators.” During Amin’s brutal regime, the executed pages were reinterpreted as “symbols of resistance to tyranny.”

Mwanga’s sexuality has often been downplayed or omitted entirely from the narrative. For instance, mainstream media coverage from 1991 to 2004 rarely mentioned that the pages refused his advances. In 2004, a more conservative Ugandan perspective emerged, with figures like the homophobic Pentecostal preacher Martin Ssempa labeling Mwanga “a deviant homosexual” who exploited his status to engage in sexual acts with his court pages. Ssempa used Mwanga as a symbol against modern LGBTQ+ activism, framing queer activists as predators.

Today, Uganda enforces some of the harshest penalties for homosexuality in Africa, with those convicted facing life imprisonment. Anti-gay activists argue that homosexuality is “Western, ‘un-African,’ and culturally inauthentic,” yet Rao points out that Mwanga’s reign is cited as evidence that homosexuality leads to depravity and cruelty.

While religious leaders vilify Mwanga, modern queer activists highlight his bisexuality as proof that queerness is natural and “African.” However, Rao describes these efforts to reframe Mwanga as “tentative and belated,” illustrating the challenges of using historical narratives in contemporary struggles for sexual freedoms.

Interestingly, LGBTQ+ activists are now exploring multiple angles within the martyrdom narrative: Mwanga serves as evidence that same-sex desire is indigenous, while the martyrs symbolize courage and self-sacrifice against tyranny, as noted by Rao.

So, was Mwanga a queer icon fighting against colonialism or a tyrannical despot ruling with an iron fist? The answer seems to be “Yes.” Real life is rarely straightforward. Regardless of whether he deserves celebration, he remains an intriguing and significant historical figure.